Charlotte: a woman smearing blood on a police riot shield. (September 21, 2016, photo by Sean Rayford/Getty Images)

Elise Greene was charged with assault on a government officer and vandalism, according to a Charlotte NBC station report, for smearing blood on officers. This seems a drastic response to a gesture that protests police violence by materializing the pain caused by this violence in the form of blood. But blood in the world of police officers is anything but a simple matter. Police work and blood are intimately connected, and I want to lay out some major aspects of this connection in order to not only explain the facts behind the police punishment for bleeding on officers, but also the connection between police work and vulnerable populations.

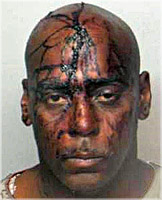

Police encounter plenty of blood. in their day-to-day work. In 2012, police in Bellevue, Ohio, charged Tiffany Pocock with assault after she spit blood on an officer and a nurse while they were taking her to the emergency room after her arrest. Earlier this year, Franklin L. Kerr sprayed blood from his head wound all over officers in Madison, Wisconsin, and KTTC quotes the arrest report saying, “With blood running down his face, Kerr shook his head vigorously from side to side spraying blood on several of the officers and throughout the back of the squad car.”

Of course officers encounter some of the most bizarre behavior and most disturbing circumstances, and these tend to make the headlines. In 2013, Officers in Mankato, Minnesota responded to a call of a father, whose son had apparently taken drugs and was slashing his own wrists and drinking his own blood. He struggled with the officers and smeared blood all over them. Nor are patrol officers the only ones who encounter blood. Clifford Wayes, sentenced to life in prison for tricking minors into producing explicit photos on facebook, managed to delay his trial by biting his cheek and spitting the blood at the testifying victims…an attempt that also added witness intimidation to the offenses and guaranteed his harsh sentence. The officers of the court had to restrain him and put a netted hood over his head. At the end of his merciless rampage, Dallas sniper Micah X. Johnson managed to leave one last message before dying: the letters “RB,” written on the wall in his own blood.

For decades, officers have been trained to see blood in different ways, as a piece of evidence that can tell much about a crime scene, but also as proof in court. Blood has been evidence in criminal trials for a long time, with each technological development in hematology labs bringing new kinds of proof. In the 1890s, Polish scientist Dr. Eduard Piotrowski created modern blood-spatter analysis in his Institute for Forensic Medicine. Attempts to evaluate the validity of statements to the police by polygraphic blood pressure measuring appear in the 1920s. Courts saw the first blood group typing and blood tests to measure intoxication in the 1940s and DNA evidence forty years later. So while officers are exposed and draw blood frequently, their work has long been concerned with handling blood as evidence, protecting it from destruction and contamination. The police tape around blood is meant to work in both directions, protecting the public from contact with blood, but also protecting the blood from contact with untrained persons.

So officers wearing gloves and masks protect evidence. Recently, however, the threat of blood seems to be on officers’ minds when they see blood as a weapon. Knowledge of blood-borne pathogens (BBPs) brings with it a fear that they can infect a person through accidental contact with mucus membranes, with the eyes, nose, mouth, or with small cuts in the skin. This is not an unreasonable fear: when police arrested Aaron Werner in Bristol, Connecticut last summer for stabbing his brother, he spit blood on an officer and claimed to have AIDS. He did not have AIDS, but had several other infectious diseases, and so the officer worried for months over whether he had gotten infected. And even officers who know they carry a BBP may wrestle with ethical and personal questions, as was the case for an HIV-positive LAPD officer: “HIV has been his secret, at first so fiercely guarded that he barely acknowledged it to himself.”

While mandatory blood tests of health care workers and officers seems like an obvious answer, we are not speaking of a problem of information. As Brent W. Moloughney explains, most patients do not recognize or report in time to allow for prophylaxis. As patients can’t always know if they have been exposed, they have to rely on health care workers: “Considering the lack of recognition and reporting of potential exposures, it is unlikely that a policy of mandatory postexposure [health care workers] testing would contribute in any substantive way to the reduction of [health care worker]-to-patient transmission of BBPs.” The unsettling power of blood brings with it the grueling terror of awaiting test results, which often have to be taken over time to gain certainty that the body is free of infection.

This fear of possible infection with BBPs is a real enough concern among law enforcement to warrant clinical studies of the phenomenon. A recent Scottish study by Karen Dunleavy et al indicates that giving officers information about exposure prior to an exposure incident did not decrease their anxiety, but that immediate response by trained accident and emergency workers and further reports to occupational health offices significantly reduced post-exposure anxiety. This confirms the findings of a previous Dutch study by Gerard J.B. Sonder et al, that found not only that the rate of exposure to BBPs in Amsterdam is low and that no seroconversions were observed, but that a robust protocol of follow-up testing and possible treatment was essential to minimizing risk.

However, beyond test results, the psychological effect is clear to me. This fear is more than a potentially distracting, even possibly debilitating side-effect of the job; fearing bodily fluids means, on some level, fearing the body that contains the fluids and in the end fearing the persons inside these bodies. Bodily fluids are psychologically unsettling, breaching boundaries, destabilizing identities. For the officer who literally and metaphorically polices the body politic, the splatter and spray present a challenge to their role as the temporary embodiment of the laws. These unruly bodies spray and spit their own essence in the face of the law, an essence that, as Julia Kristeva reminds us, belongs to the realm of the abject, that ultimate other that makes us possible. Like red lava erupting into an ocean of blue, the clash of metaphorical roles is a spectacular moment of anxiety.

Beyond this unsettling undercurrent, however, we also know of the social dynamics blood brings into play, compounding bio-medical anxieties with social ones. Currently there is a great deal of discussion surrounding the disproportionate use of police force against persons of color and persons with disabilities. We understand that police work changes drastically when officers bear prejudices against persons. Of course it would be impossible to be prejudiced against the blood we all carry inside us, but we also know that blood is ascribed to groups and seen as different, separate, alien. In the context of race, we know that persons of color have been fighting racism linked to blood for hundreds of years. To regard the blood as black persons as dangerous and contagious and to punish someone like Elise Greene for smearing blood on police equipment may therefore be a reaction to work hazards in the daily lives of officers, but such punishments cannot be read in isolation from their historical echoes of racist tropes of so-called black blood, of the one-drop-rule, of miscegenation. Police work embodies the state’s power to control and force populations and while officers need to understand the risks of BBPs, they also need to understand the symbolic value their actions carry.

Beyond inter-personal relations, this simultaneously medical and social aspect of blood can have very tangible, real results in the ways blood structures the interaction between officer and citizen. For one, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration has claimed authority to regulate contact between infected human beings and persons who work with them, an effort which Paula E. Berg sees critically, not least regarding social justice concerns: “as previously stated, when regulations leave employers or employees to their own devices in making risk assessments, or when they do not mandate anti-discrimination education for employers and employees, increased discrimination against members of historically disfavored groups is a foreseeable unintended consequence. Therefore, feasibility under the Act must also be judged by whether workplace contagion standards include adequate precautionary measures to ensure that day-to-day decisions about risk acceptability and risk reduction are equitable. Specifically, contagion standards must include explicit, detailed, individualized, and scientifically based criteria for determining risk acceptability and they must require that employers and employees receive anti-discrimination education.” By focusing on BBPs as an occupational health issue, the OSHA regulations dehumanize both the infected person and the officer, potentially focusing on the former as a biopolitical threat and the latter as a worker handling dangerous materials, not a person trying to help another person.

Police work itself directly influence the presence of BBPs in the populations that police encounter and can in effect create a more hazardous and anxiety-driven work environment. As UCSD’s Steffanie A. Strathdee et al point out, “arrests for drug possession, soliciting bribes and unlawful confiscation of syringes can influence where, with whom, when and how PWIDs consume drugs. Policing practices can directly affect PWID by discouraging them from carrying their injection equipment or injecting hurriedly in the street, in shooting galleries (where used needles are rented or sold), or by injecting in less visible—and higher risk—sites on their body, and seeking out ‘hit doctors’ who help them inject drugs. In these situations, PWID are at higher risk of acquiring HIV and other blood-borne infections such as viral hepatitis or overdose mortality.” So police actions that might be politically billed as “tough” on drugs may in the end only put police officers at risk in their daily work, further distracting them, and raising anxieties. Confrontations between police officers and such already vulnerable populations will escalate, leading to further incidents of officers insisting on severe punishments for persons endangering them by bleeding on them.

In this context, charging persons for bleeding on officers can lead to more confrontations if the persons were not bleeding before encountering the police, when the contact with blood results from police violence. For example, the Inkster, Michigan officers who clobbered Floyd Dent in 2015 seemed amused by their excessive violence as they cleaned his blood off their uniforms with disinfectant. While the disinfectant seems to indicate their desire to reduce the medical threat Dent’s blood posed, that was clearly not their primary concern. Likewise, in 2009, Officers in Ferguson, Missouri, charged Henry Davis with four counts of destruction of property for bleeding on their uniforms from wounds sustained during a beating by the police after a traffic stop. He pleaded out on two counts and traffic violations, paying $3,000 in damages.

Davis’ 2010 suit for assault against the officers just got reinstated in a federal appeals court. Police violence leads to blood shed, and insofar Greene was right to use her blood as a sign of protest.

Somewhere between Dexter and Blue Bloods, between the blood-flinging perp and the blood-dripping victim lies the truth of blood in policing, a complicated reality of real and imagined threats, of a discriminating understanding of blood and discrimination against persons, of protecting the public and protecting oneself.

When Elise Greene was charged for smearing blood, she entered the complex of criminalized behaviors that reaches deep into our bodies. But the story of what blood is and is never limited to just one aspect, and while protestors must know the risk they take in making their bodies, their blood a weapon of protest, police officers must recognize the real connection they have to blood and how their actions directly influence the ways we encounter blood.

2 thoughts on “Bleeding Blue: Police Work and the Bodily Fluid”